Note: this post is a part of a crash course in journalism. If this is the first post from the series you encountered, it is highly recommended to start the course from the beginning. See index of previous lessons at the end of the post.

This lesson, the one before the last lesson of my crash course in journalism, is about my favorite word, “curiosity”, and about another word that I like very much “complexity”.

In this course, I talked much about the truth, and about how journalists have to be committed to it. But the truth is (pun intended), that we don't know and don't understand most of what is going around us.

Our brains are wired to cope with either very simple things or with very large systems, in which the law of big numbers make things appear simple. Everything in the middle - that is most of everything - is simply too complex for us to comprehend. So how do we get along? The answer is this: We make up stories.

Stories take complex concepts and pack them into simple terms. They allow us to understand the general framework of things without having to dive into the details. If we believe in the story, we just accept it's underlying assumptions, without asking too many questions. This ability to use stories as a mean for social cooperation in complex situations, is what distinguishes us as humans from other species, but because it is built so deeply into our psyche, it can be easily used to manipulate us and control us.

Yet there is something more that those who wish to control us have to do in order to make us believe their stories too easily - they have to make us lose our curiosity.

Unlike storytelling, curiosity is not unique to humans. It is rooted in our primitive instincts, and this is why the first story that any tyrant tries to sell us, is that we have to restraint those instincts. A rhetoric that tells us that we must descend above our human nature or put more subtly, “be better than others”, is the emblem of tyranny. Why is it so important for them? Because they don't want people to be curious, to ask “Why?”.

So journalists, as those who often are more capable than others to tell and proliferate stories, always have to ask themselves, “are we aiding the process of killing curiosity? Or are we acting as a defence against it?”

Because a good story can go either way, and it is up you to decide.

Next week, we are going to have the last lesson in the course were we will be wrapping everything up.

Index of previous lessons:

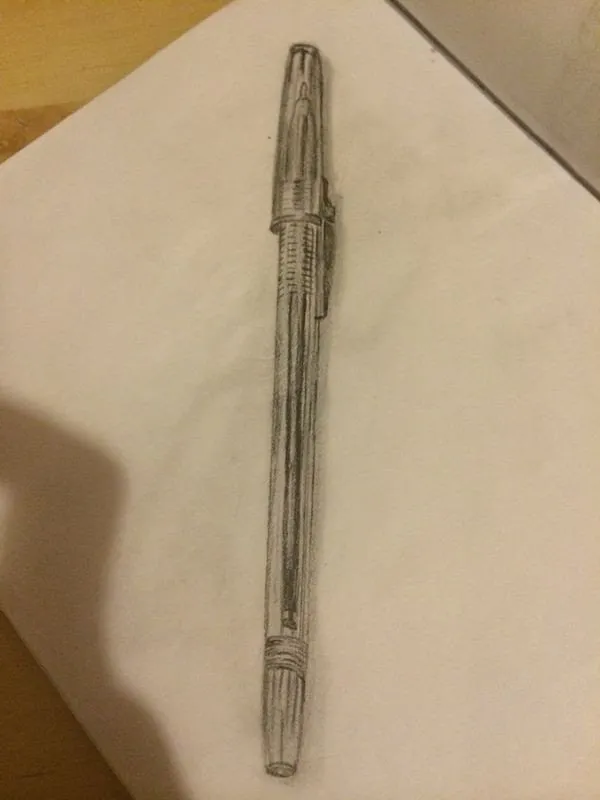

Lesson number one: Buy a notebook

Lesson 5: Using your notebook in the field

Lesson 6 : "The something else"