Have you ever been discussing an idea with someone where you reach an impasse of disagreement, and one or the other of you declares, “I’m entitled to my opinion”? When I sat down to write about this topic, I was going to give a surly, condescending rant about how obviously stupid this phrase is. But as I thought about it, I realized it deserved a more serious examination.

Source

DISCLAIMER: The following is my opinion.

Most of us are taught that statements can be broken down into two categories: facts and opinions. Facts are objective. They are true despite what we think or believe, and they are verifiable out there in the world. Opinions are subjective assertions that may or may not be true. People have conflicting opinions, and this is to be expected since opinions by their nature are not verifiable with certainty.

However, this dichotomy camouflages a more complex reality. And in this post-fact world that we seem to find ourselves living in, the resulting confusion causes more and more harm.

I'm going to suggest that there are several distinct types of opinions, each of which has different characteristics, and that they should therefore be approached differently. Further, it is the conflation of these opinion-types that causes confusion in communication and makes agreement much more difficult, especially when it comes to hot-button topics.

Here are my three categories of opinion (though further thought may suggest additions):

- Opinions of taste

- Opinions of fact

- Opinions of prediction

Opinions of Taste

Opinions that fall into this category are the ones most people would identify as opinions. Massages feel good. That rainbow is beautiful. I like chocolate, and vanilla can suck it!

Source

Here's the funny thing about this kind of opinion: it is verifiably true with certainty. Such statements say little about the thing discussed, but instead say something about the person making the statement. You like chocolate. Your tastes are defined by your subjective experience, so there is no outside authority or fact that can change the truth of that experience.

Such simple opinions of taste are probably the only cases where "entitlement" is relevant to opinion. Example: Sam declares that chocolate is a horrible scourge upon society. Bill says he likes the taste of chocolate. Sam calls Bill a savage and claims there is no good reason for anyone to like chocolate. Bill wins the argument by saying, "I am entitled to my opinion."

Sure.

But very few people get into heated debates about their positive or negative experiences with chocolate. We instinctively recognize that simple opinions of taste have no real power to cause controversy.

Another way to define opinions of taste is to recognize that they are always statements that express VALUE. Value by its nature is subjective, and only a subject can assert the truth of a value statement. X is good. X is bad. What such value statements really mean, however, is "X is good for me" or "X is bad for me". All value is defined by perspective.

Now look, the perspective in question may be as large as humanity itself: Ingesting cyanide is bad. That's true for every person on the planet. Other questions of value probably run up against a more divided perspective: Lesbian zombie comics are good. While the value of cyanide is more or less defined by universal biological qualities, the enjoyment of lesbian zombie comics is determined more by one's cultural experience, which can differ from person to person.

Hey, if Tom Hanks likes it...

But not all opinions of taste are so simple and verifiable. "I like the graphic novel, Lesbian Zombies from Outer Space," and "Lesbian Zombies from Outer Space is a great graphic novel" are both opinions of taste, but they are making two distinctly different claims. The first claim is a statement of your specific experience with a particular book. The second statement claims that the book is great, and this is a status that goes beyond one's individual reaction to it. To make this assertion, you must have a pretty good understanding of what graphic novels are, and what qualities make them good or bad or exceptional. The latter claim, in fact, is a much more complex assertion, since it sits atop a set of assumptions about the thing in question. Said another way, the statement that a graphic novel is great rests upon certain premises about which the speaker assumes there is some agreement.

Forget lesbian zombies. Let's talk about something I know you have an opinion on:

Trump is a great American President. That is an opinion of taste. But the reason for a person's belief in such a statement is not as simple as licking some chocolate ice cream and reporting how it makes you feel. One first has to have a set of beliefs regarding what a president is, what a president does, what behavior in that position benefits America, what behavior in that position benefits you as an individual, what previous presidents did before, and how the current behavior, and its resulting effects, compares to those previous presidents, etc. Some of these underlying beliefs are opinions of fact, and some of them are just more opinions of taste.

The point here is this: no one can verify the truth of such a "high level" opinion until he first examines the underlying opinions and assumptions that support it; and no one with intellectual honesty can make such a claim without first examining the reasons behind it.

Of course, the reverse is also an opinion of taste: Trump is a shitty American President. I'll let you judge which is the opinion that more likely coincides with reality.

Opinions of Fact

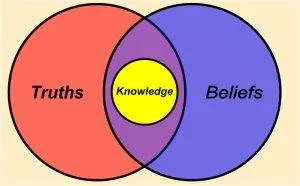

Without wishing to get caught up in the weeds of relativism, I've got some possibly disturbing news: all facts are beliefs; and they are beliefs in the same way, though perhaps for different reasons, as opinions are beliefs. Whatever we assert to be true, we assert to be true because we believe it to be true. Paris is the capital of France. Two plus two equals four. Humans are natually bipedal. These are all facts. These are all true. These are all easily and unequivically verifiable. But it's important to understand that they are all still beliefs.

Why is this important? Because many people seem to have reached the flawed conclusion that "beliefs" are somehow less valid or valuable than "non-beliefs", whatever they are. But there's actually no such thing as a "non-belief" (a concept I just made up), because all assertions of truth are by definition beliefs. We just like to dress up these beliefs with words like "knowledge" or "fact" or even "truth" itself.

Source

Don't worry. I'm not going to insist that we label such basic facts as the capital of Paris "opinions of fact", even though they do seem to have a lot in common with the low-level opinions of taste I mentioned above, like value judgments about chocolate.

Once we move away from the easily verifiable, however, we get into the territory of opinion, whether we like it or not. Any statement of belief that does not make a value judgment (or does not make a prediction about the future, as discussed below) is an opinion of fact. Opinions of fact attempt to describe and explain the world around us.

Here's an example: Vaccines cause autism. This is an opinion of fact. It makes a claim about the world - that some quality of vaccines can cause autism in children. Of course, the reverse is also an opinion of fact: Vaccines do not cause autism. The truth of these statements is not as easily verified as the capital of France. Yet, with enough time and effort, they can be proven or disproven.

The problem with opinions of fact is not that they are unverifiable; it's just that they are usually difficult to verify with certainty. And even when they are verified with certainty for some people (Vaccines don't cause autism, fuckheads!), others are not convinced by the evidence, or refuse to be convinced.

Now we start to see the interplay between opinions of fact and opinions of taste. When talking about vaccines, some parents will say that vaccines are bad, and there's no way to argue against that claim until and unless you overturn the underlying opinion of fact regarding autism. In truth, if two people are arguing about the value of vaccines without examining the root opinions of fact, it almost makes sense for one to shout out their entitlement to their opinion. At least insofar as they have been offered no reason to change their view.

Sometimes, though, the causal interplay can go in the opposite direction. Consider racism. All people of X race are bad or inferior. This is an opinion of taste. And if one holds such an opinion, she will be drawn to statements that support it, such as X race naturally has lower IQ, X race are all thieves, etc. These latter statements are all opinions of fact.

Well, shit. This is going longer than expected. I think this is going to require a Part II! I have more to say about opinions of fact; we'll touch on opinions of prediction; and then I'll wrap it up with a conclusion so astonishing and so satisfying that your perspective will be changed forever. Check back soon.

Recent posts:

- Socrates and Individualism, Part I

- Reason and Emotion: The Children of Desire, Part I

- Trial of Socrates: Teaser Scene Motion Comic

- Lesbian Zombies from Outer Space - Latest pages

Art courtesy of @PegasusPhysics